The Other History of the DC Universe #1 by John Ridley, Giuseppe Camuncoli, Andrea Cucchi, José Villarrubia and Steve Wands was released on November 24, 2020, after being in the works behind-the-scenes for years. The series, showing key events in DC Universe history from the perspective of characters hailing from traditionally disenfranchised groups, starts with an issue focused on Jefferson Pierce, detailing his experience as Black Lightning—one of DC’s first Black superheroes—juxtaposed with America’s history of real-life violence and discrimination against Black individuals.

When the series was originally written and conceived, no one involved could have known exactly what the world would look like when the first issue went on sale, following months of unprecedented protests against white supremacy and police brutality sparked by the May 2020 murder of George Floyd. But as Ridley himself puts it, “none of this is new.”

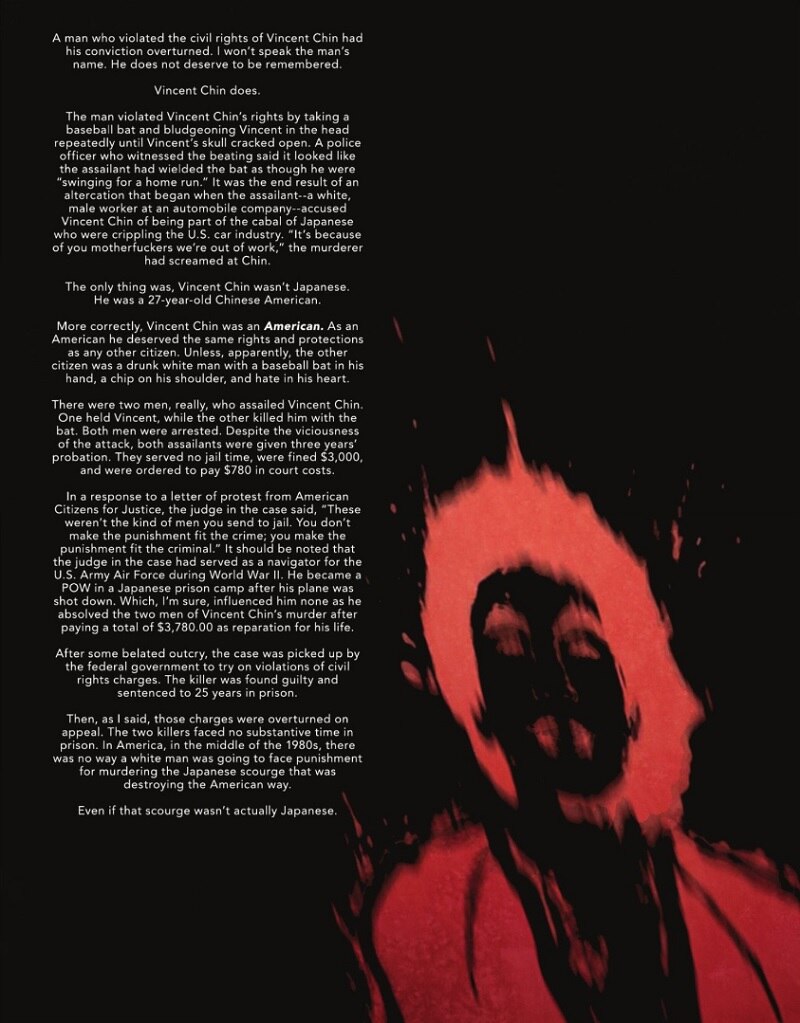

Four months later, The Other History of the DC Universe #3 is now in stores, this time focused on Tatsu Yamashiro, better known as Katana. Tatsu is historically most closely associated with the Outsiders, but has been recently seen in comics and film as a member of the Suicide Squad. The latest installment of the five-issue DC Black Label series again delves into real-life events, including the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin—a victim of inexcusable racial paranoia and grievously misplaced anger. This issue, again, is heartbreakingly, frustratingly relevant, coming after a year of skyrocketing hate crimes against Asian Americans fueled by xenophobia and racism by people desperately looking for a group to blame for the ongoing pandemic, despite the association clearly not being founded in reality.

Specifically, The Other History of the DC Universe #3 comes two weeks after a series of mass shootings in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia, where eight people were killed, six of whom were Asian women. The parallels between recent events, the murder of Vincent Chin, and a number of tragedies in the thirty-nine years in between are readily apparent. Though there was no way to predict what was coming, the painful pattern of violence is as recognizable as it’s ever been.

“It didn’t start yesterday,” Ridley said. “It didn’t start a year ago. It’s been going on.”

DCComics.com spoke in-depth with Ridley about The Other History of the DC Universe #3, the heartbreaking relevance of the issue, and why Katana was the right character to tell the story of attempting to be a hero amid the oppression and discrimination of the 1980s.

The Other History of the DC Universe #3 is an impressive issue in all respects, and of course the heartbreaking thing is that none of us had any idea just how relevant this issue would be, coming out when it has. When you read the page about the murder of Vincent Chin—a real-life event from nearly forty years ago—and the circumstances of what happened, it’s eerily similar to recent events. What’s your state of mind on this comic coming out now, given what has transpired, and the maddening reminder that these tragedies keep happening?

It breaks my heart. This is the third issue, we’ve got a couple more coming out. The first, about Jefferson Pierce and his perspectives on race, came out in the wake of the reckoning we had following the execution murder of George Floyd. People were saying, “Oh my god, how did you know? How do you feel?” Now it’s the third issue, and it’s the same thing. My heart is broken.

I’m always proud when I have the opportunity—whether it’s this, whether it’s 12 Years a Slave, whether it’s American Crime, Guerrilla—to add to these necessary conversations, and in some cases even force conversations, on different marginalized communities. It breaks my heart when the work that you do comes out at moments and people ask, “Well, how did you predict this?” I didn’t predict it, but it’s never gone away. It gets modulated—up or down, louder or more softly—but violence against Asian-American communities, bigotry, going back months and months when people were openly misnaming the virus that we’re going through and creating an enemy for their own purposes. Then we get here.

“How did this happen? This isn’t us. This isn’t America.” Well, yes it is. It painfully is. And it’s not new. You go through the book. The Chinese Exclusion Act. Or Executive Order 9066. Or Vincent Chin. Or what happened in South Central LA—the stress points between the Black community and the Asian community. None of this is new. I’m never surprised by the violence, by the hatred, by the bigotry that exists. I’m surprised when the supposedly good, reasonable people are surprised that it’s happening.

I remember the first time we talked about this series was last year, against the backdrop of everything you just noted. It’s almost debilitatingly discouraging when you think about how these things keep happening. Something that’s notable about this series is that it’s showcasing different perspectives in multiple different marginalized, othered groups, from in and outside your own lived experiences. Why was it important for you to take that approach? And what was your process in doing that?

Let me start with the second part first. You get anxious. We live in a world now where we absolutely are, and should be, very cognizant of who’s telling stories—both for the veracity and also making sure that we give the opportunity to people who have a lived experience that is much more close in line with the characters, to weave their lived experience into the fabric of those characters.

You start with Jefferson Pierce. I felt very comfortable writing that. His age as he’s telling this story, his experience, it mirrored mine. I didn’t have a problem with that. With Mal (Duncan) and Karen (Beecher-Duncan), obviously I’m not a Black female, but I’ve grown up around them. I’ve been around women of color my entire life. I don’t want to suppose that being around is the same as living, but a young Black man, his partner in life, their experiences, I felt like, okay, I could accomplish that story.

You start getting into Tatsu and even though there are many aspects of her life that, again, have surrounded my lived experience—with my family, with my family’s family—you are getting into a space where, okay, this is not me. One of the things that remains a guiding principle, part of the reason I’m sitting here and you and I are having this conversation, is because there were so many people—yes, historically, they’ve been largely white men—who have added to the fabric of storytelling that helped inspire many people, and me in particular. I think of Tony Isabella writing Black Lightning—if it weren’t for him saying at some point, I’m going to write this character of color, and write him to the best of my ability in a way that’s entertaining and that he’s just as exciting as any other hero, and maybe it’s going to inspire somebody else to do it… I get to be part of a continuum of storytelling where now maybe I’m inspiring somebody. I hope I’m doing my best work. I hope I’m honorific of people’s experiences, but if nothing else, I hope certainly in a positive way, I’m inspiring somebody else to say, “Okay, you know what? This is a good story, but if I wrote it and I added my lived experience, it could be even better.”

No, I am not a female Japanese national telling this story. But at the same time, I was not a Black slave in 1849 when I wrote 12 Years a Slave. All of it is saying, “This is less about me, let me go on a listening tour. Let me go on a reading tour. Let me sponge in all of these things.” Vincent Chin’s murder—I remember it. It was impactful for me back in the day. It’s not an accident that it’s in there. Tatsu’s going to comment on this. Tatsu’s going to comment on the stress points in Los Angeles between Blacks and Asians. She’s going to want to go visit Manzanar, sit in the space and wonder what it would have been like to be Japanese in America in the 1940s. She arrived at DC in the 1980s, and that was not a great time for Japanese nationals to be in America. There’s some supposition, but a lot of it is taking things that exist, listening, putting emotions that are true human to human to human, and putting that all together and hoping and believing that you’ve created something that will entertain everyone, but hopefully inspire the next generation.

Many fans will know Katana mostly as a character in team books like Batman and The Outsiders and Suicide Squad. This issue really delves into her psyche and details her personal perspective. What potential did you see in the character that made you certain she should be one of the handful of characters you focused on in this book?

I saw the potential in every one of these characters. Every one of them has been around for decades and they’re incredibly durable. And they have not been marquee characters, but they’ve been witnesses to an incredible history. If you talk to anybody who was there in the room where it happened for all of these amazing things, you know their story is bigger than just being a side character. They were there for a reason. They were there because they were trustworthy as a team member, they were there because they were durable, they were there because they had something to add. When you go through these comics, even though they may not have been the lead characters in some of these stories, the moments they were around were pretty monumental.

It was an honor to take every one of these characters and elevate them to the place where any writer can come in afterwards now and see the work the other writers have done through history. If this was where my career ended, by elevating Jefferson, Tatsu, Mal, Karen—Renee (Montoya) probably didn’t need it, she’s pretty durable, but she’s great and certainly deserves it—and Anissa (Pierce); if that were the end of my contribution to pop culture, I’d retire a happy man.

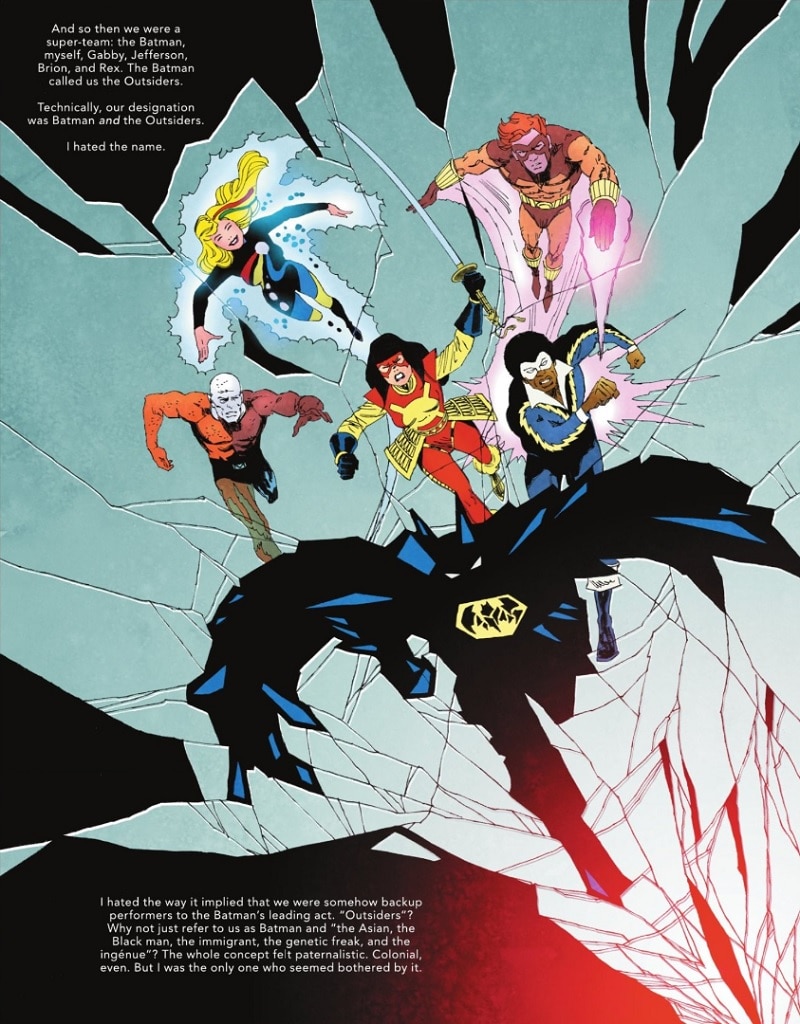

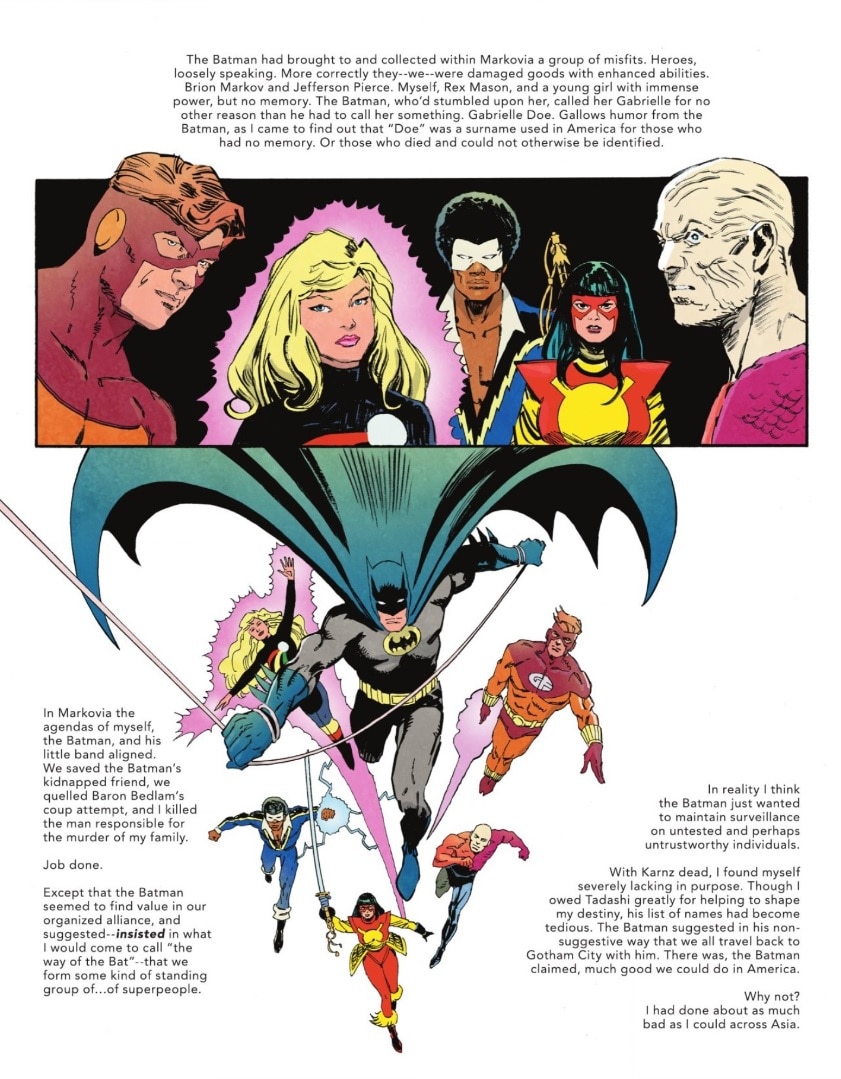

Going from characters that may be slightly under the radar to one everyone knows, I’m fascinated by the view of Batman in this story. One of the most compelling things about the series as a whole is that it takes a critical look at not only at real world history, but DC Comics history. I loved the part where Tatsu questions the name “Outsiders,” and how that’s kind of an insulting name for that group of characters. What was it like taking a character like Batman, and elements of DC history that fans may have taken for granted over the years, and dissecting it and putting a different perspective on it?

I felt very comfortable doing it. With Batman, with Superman, it’s not like I said, I’m going to make these guys cyphers for the worst of the worst of American perspectives. But I think there’s a reality that it’s getting harder and harder for people to deny that there are biases that are baked into the system. We see that with the pandemic when it disproportionately affects Black and brown people. Certainly, the previous summer with the reckoning on race and policing. Now, with what’s going on in Asian communities and the violence directed towards them. Even with the women who were executed, they were working in industries that are preyed upon. People who have to live in the shadows. Far too often that’s immigrants from Asian nations.

It’s just getting harder and harder to deny these things. For me, it was just about saying that Superman and Batman, there’s a certain level of privilege they have in being who they were. Superman’s not an illegal immigrant, he’s not a non-documented individual, he’s an alien. But he reflects the prevailing culture and he got to represent America more than natural-born (individuals). Part of that was truly an expression of immigrants of that age, saying that maybe we’re different, but we love this country as much as anybody else. When we talk about privilege, that’s what we’re talking about—not that you’re bad because you have privilege, but acknowledge that being a straight white male, there are certain things that you have that other people don’t. Being a rich white male, there are certain things you have that other people don’t.

I really appreciate that you pulled out that line about the Outsiders, but Jefferson didn’t have a problem with it. Tatsu did. It’s not just us against them. Even among Black, brown or Asian folks, we see the world differently, too. That’s why it was very important to me. Ultimately, Tatsu was like, “You know what? I am an outsider, but that doesn’t bother me anymore. I’m going to pick up that mantle and say, you don’t get me, but I don’t need you to understand me.”

I try to not assign blame, or say, “the evil person in this book is going to be Superman. The evil person in this book is going to be Batman.” It’s society. It’s structures. It’s historical norms. Those are the bad things. It’s about perspectives.

At the end of the day, I never got any pushback from DC because it was equal in its dispensation of the idea that ultimately what we need to do is be able to see ourselves in others. To me, it was just treating all of the storytelling as very mature. Mature doesn’t just mean bad language, extra violence and sex. Mature means treating your readers like adults.

Looking at this issue and the series as a whole, the work the art team of Giuseppe, Andrea and José are doing is striking. In issue #3, it’s clear how well they capture the ‘80s DC aesthetic, but with such a modern approach in the composition. Then the issue progresses into the ‘90s and present day and the art evolves with it. What’s it been like working with this art team, given that by nature it presents a unique challenge in spanning so many eras and that it’s not a standard sequential, panel-by-panel format?

They have been so amazing in every regard. “Giuseppe, what inspires you in the prose? What is your takeaway?” The art would come back and I would be surprised by what he chose to pull. By the flow. How he pulled the script pages out. He would do deep dives into the historical art—"I need it to look like this; it’s going to look like this artist back in the day.”

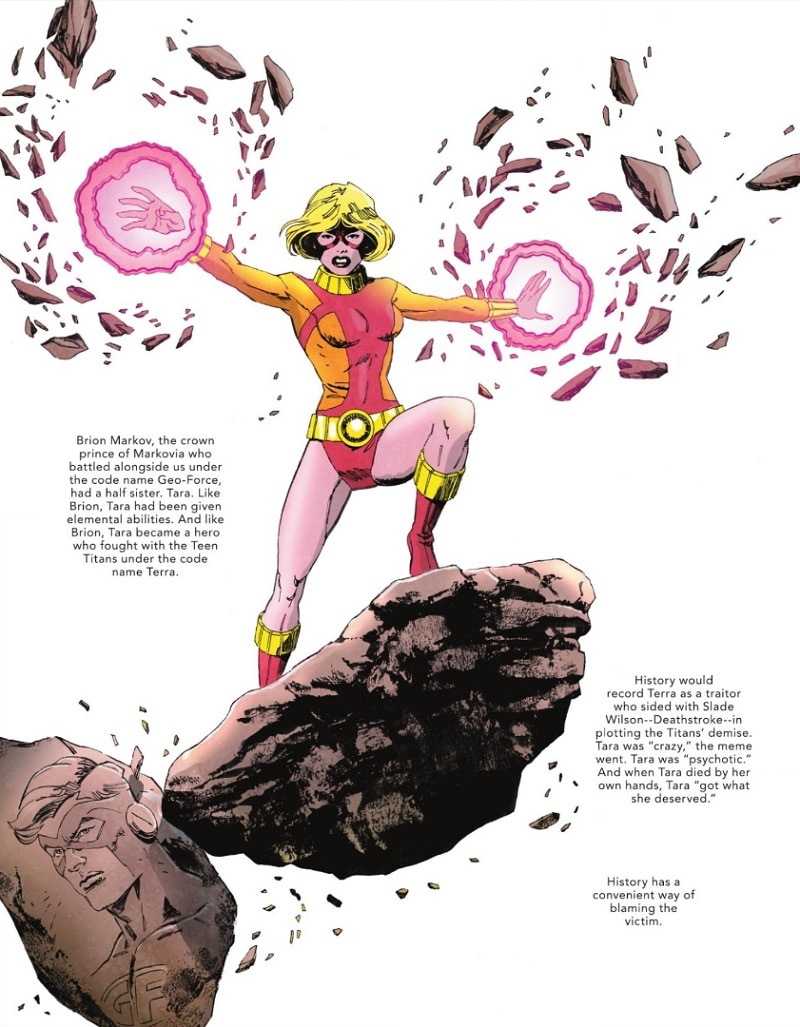

In the third issue, there’s some imagery of Terra from the Titans where it looks like some images from back in the day, but she’s holding herself a little differently, because we really leaned into the fact that Slade was basically assaulting an underaged girl. So rather than the imagery where Terra’s head is held up and she’s smiling, she’s got her head sunk and she’s weeping. To me, it’s those subtle things. You can go back into your Titans books and find that moment, but the lens has shifted.

All of the work—the finishing, the inks, the coloring, the lettering—it’s really weird to work on a project for three years and every one of these issues was down to the wire because nobody wants to give up. Nobody wants to say, “Okay, that’s good enough.” The three of those individuals—Giuseppe, Andrea and José—are just amazing. It’s all day, every day. This has been one of the projects I’m sincerely most proud of that I’ve ever been a part of. Everybody treats it like we’re really writing oral histories. I just cannot say enough about the team, because it has been a real team effort.

As noted, this series has been in the works for a long time and now we’re roughly halfway through the issues. What has it meant to you to finally have this out in the world and people are seeing what the team has been working on for so long? Knowing that it’s been an unconventional type of comic in many ways—from format, to content, to theme—how does it feel to see people pick it up and get it, and embrace what you’ve been working on for so long?

I couldn’t be more proud and I couldn’t be more pained. I’m so proud of the work, I’m so proud of the team. Everybody—the editors, everybody at DC—I don’t think they get enough credit for what they wanted to try to do, starting three years ago. This is not corporate do-goodery, they made a decision three years ago to lean into race, orientation and gender. Every step of the way was just push it, push it, push it. Let’s do more. Let’s make it better. I’m proud of all of that.

It really, genuinely pains me, to the point that I could literally start crying right now, that this book is coming out right at this moment. I’m proud that we’re hopefully, at whatever level, forcing conversations. It breaks my heart that a story about Vincent Chin, who deserves for people to know his name—I’m not going to say the names of the perpetrators, they should be consigned to the potter’s field of history. That a story about Vincent Chin is coming out at a time like this just breaks my heart. I’m happy that we add to the awareness. It didn’t start yesterday. It didn’t start a year ago. It’s been going on.

How does it feel to know we’re coming out in a moment that hate creates? It feels terrible. I could not be more proud, I could not be more pained. If there was a piece of art or literature that was going to change the world, somebody else would have already created it. I do hope that for people who have the capacity to understand that this stuff needs to end, that this will help them understand that this is cyclical.

You look at what Watchmen on HBO did—some people didn’t know about Tulsa. It took a TV show to educate people. I hope for a lot of people that right now genuinely want to understand that this is an opportunity to really grasp how we got here and why Tatsu is such an amazing character in the DC fabric.

The Other History of the DC Universe #3 by John Ridley, Giuseppe Camuncoli, Andrea Cucchi, José Villarrubia, and Steve Wands is now available in print and as a digital comic book.